Those who know me well know that I often have zero interest in popular culture. Sure, I like a good ballgame and follow my local sports teams with more than a passing interest. But when it comes to celebrities, television, "human interest stories," trivial banter, and famous-people gossip, I'm usually tuned out deliberately. Anything I do end up learning about these things is often because our society is so saturated with this crap that even people like me aren't immune from it.

Take the recent "Obama party chasher" couple. Apparently, these two have spent a long time cultivating a high-rolling, pseudo-famous image, to the point where they have now entered our public consciousness by breaching White House security and living it up with the leaders of two nations. Besides the general concern I have for our President and his family, who will probably wonder about security at all future events, I find myself in awe at the level of meaningless nonsense people have deemed important in their lives.

I came upon this relentless article by writer Chris Hedges about the addiction Americans have to pop culture and various other trivial bits of information. He writes:

Will Tiger Woods finally talk to the police? Who will replace Oprah? (Not that Oprah can ever be replaced, of course.) And will Michaele and Tareq Salahi, the couple who crashed President Barack Obama's first state dinner, command the hundreds of thousands of dollars they want for an exclusive television interview? Can Levi Johnston, father of former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin's grandson, get his wish to be a contestant on "Dancing With the Stars"?

The chatter that passes for news, the gossip that is peddled by the windbags on the airwaves, the noise that drowns out rational discourse, and the timidity and cowardice of what is left of the newspaper industry reflect our flight into collective insanity. We stand on the cusp of one of the most seismic and disturbing dislocations in human history, one that is radically reconfiguring our economy as it is the environment, and our obsessions revolve around the trivial and the absurd.

Of what value is knowing what's "really" on with Tiger Woods? How will knowing that, gasp, Mr. Woods is a flawed guy make the world a less violent, more compassionate place? In fact, how much of wanting to know the "dirt" about famous people is just an effort to feel smug about yourself, to be able to share a moment of glee with your friends at the expense of famous person X? I can hear the emphatic cries now: "I told you Tiger Woods wasn't perfect! I told you so!"

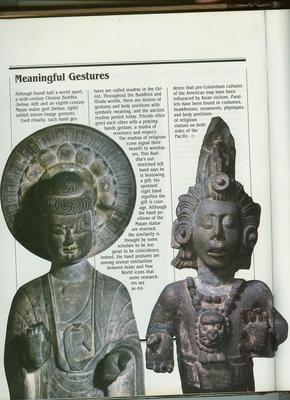

Haven't we heard similar comments about Buddhist teachers whose squeaky clean images are suddenly cracked in half by some scandal. It's as if we have plugged our ears to every teaching the Buddha gave about about the fluctuating, unstable nature of people and their characters.

Take a deep breath after reading the following statement from Hedges, which I think points to the grave trouble that comes from an emphasis on the trivial and meaningless:

Celebrity worship has banished the real from public discourse. And the adulation of celebrity is pervasive. The frenzy around political messiahs, or the devotion of millions of viewers to Oprah, is all part of the yearning to see ourselves in those we worship. We seek to be like them. We seek to make them like us. If Jesus and "The Purpose Driven Life" won't make us a celebrity, then Tony Robbins or positive psychologists or reality television will. We are waiting for our cue to walk onstage and be admired and envied, to become known and celebrated. Nothing else in life counts.

Now, I don't think everyone in the U.S. has a dream to become a celebrity, but certainly there are a lot of us who do. Why else would reality TV be so pervasive, to the point where people like the parents of the "Balloon Boy"(I couldn't escape that one either) would feel entitled to involving real public officials and police officers in a chase for their future fame? Ir would ignorant, in my opinion, to assume that the Balloon Boy scandal, or the White House Party Crashers, are simply isolated incidents of hubris.

Take the show "American Idol," just to give one example. During the last season of the show, 624 million votes were cast for the contestants of the show. In fact, during a single episode in May 2009, 100 million votes were cast. Think about that - almost 1/3rd of the nation felt it was "important" enough to speak their mind about someone singing a pop song on TV. Not pretty.

I could probably fill pages with theories about why all this has come about. Everything from a void of meaning in people's lives to the end logic of a capitalist society might apply. I'd like to think that Buddhist teachings might be of some help, but some days, I'm not sure if even Manjushri's sword could cut through this pervasive, collective delusion.

Maybe it's like chopping down a tree with an axe in that it's going to take many, many hacks from a hell of a lot of us, repeatedly, to shift the madness.

There's nothing new about cults of celebrity and the fantasies that drive them. But when you look at the cultures that became consumed by variations of this theme, such as ancient Rome, it's hard not to see what's coming next: collapse and misery.

In a way, we're already seeing signs of it. People going on shooting rampages. An expansion of overt racial and religious hatred. The commodification of anything and everything, including our deepest, most intimate ethical and spiritual values. And I'm sorry folks, but these aren't just symptoms of a temporary recession: they are balls of collective karma we have been rolling down the mountain for decades.

Not too long ago, I got into an argument with a friend about the level of talent on our local American Football team, the Minnesota Vikings. He said they weren't really as good as their record is, and I disagreed. This went on for a few minutes, some back and forth defending our points with trivial minutia, until I realized that I just didn't care. It didn't matter whatsoever whether I was right or he was right.

And yet as I write this post, I am aware that even I have a bit of this addiction floating within me. This is the power of collective addictions - they have an impact on even those who participate the least in them. May we each wake up, and may we work together to help each other wake up, from these dangerous dreams we cling to.